The South End Speaks

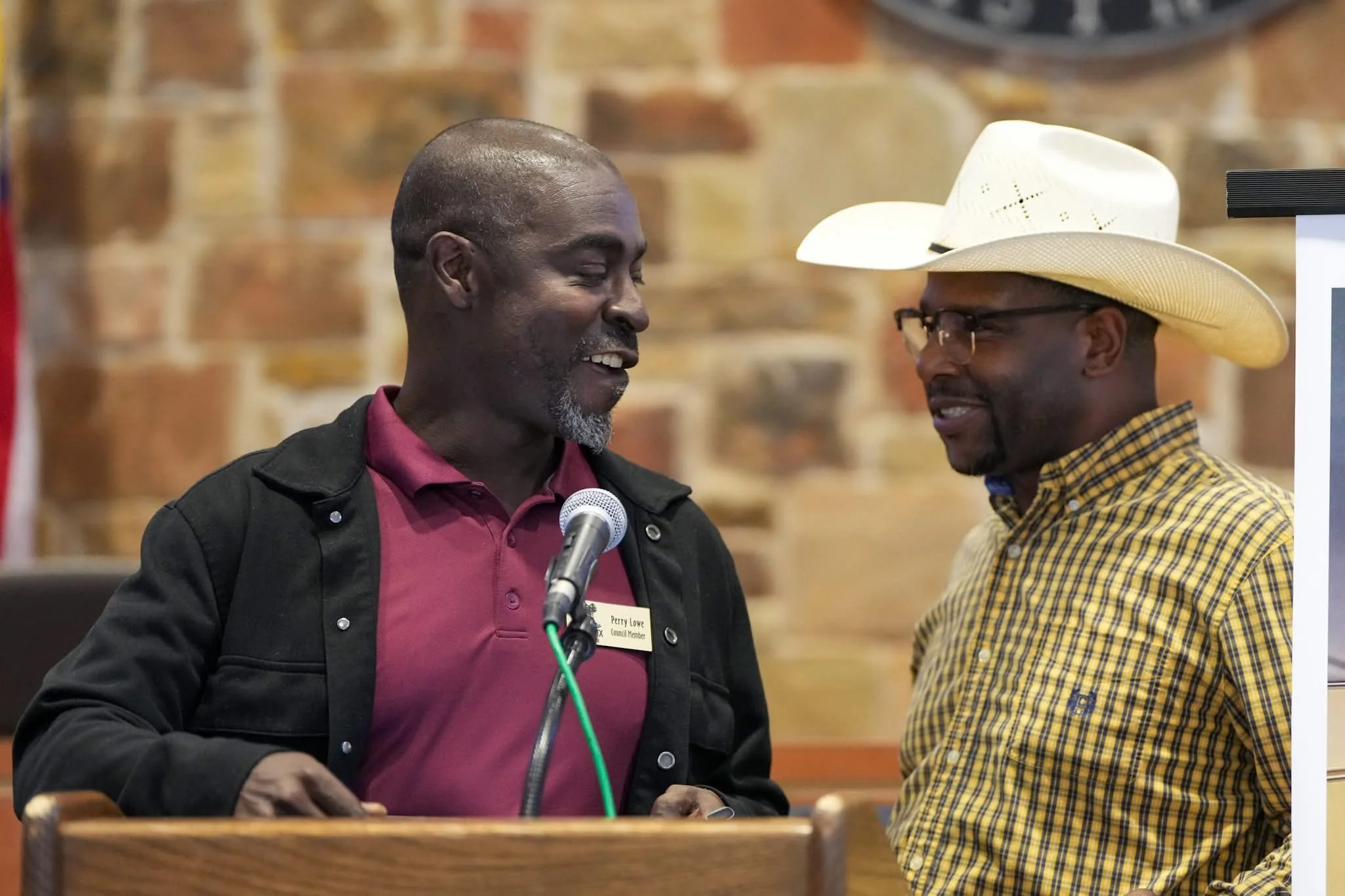

Mayor Ishmael Harris and Council Member Perry Lowe

Photo by Robert “Doc” Washington Photography

The summer heat had not relented by the evening of July 9, 2025, but it did little to dampen the energy that buzzed throughout the Bastrop City Hall. Rows of chairs filled quickly with elders, youth, pastors, teachers, and neighborhood families. Some carried quiet memories of old Bastrop. It wasn’t just another meeting; this was a reckoning. The people of Bastrop’s historic South End had come together not only to remember, but to reclaim.

The town hall had been called to explore the creation of a formally recognized African American Cultural District centered on Bastrop’s South End—an area dense with historic Black churches, family homes, and the once-segregated Emile School. But the conversation quickly evolved into something far deeper: a storytelling revival and a communal declaration of purpose.

Mayor Harris opened with a nod of humility and pride. "This began as a seed," he said, gesturing to the packed room. "But I knew it needed to be passed on to someone who lived this history." He passed the microphone to Council Member Perry Lowe, who stood with a visible blend of emotion and resolve.

"Goal number one is preservation," Lowe said, steady and clear. "We are here to protect the sacred sites of our community: Emile School, Macedonia Missionary Baptist, Paul Quinn, the Kerr Center, and the Kurt Wilson Homestead. But this is also about cultural recognition, education, economic opportunity, and, most importantly, healing."

Applause rippled across the room. These weren’t distant objectives; they were the embodiment of lived experiences, generations of them. Each speaker added a stitch to the patchwork of memory that began to take shape over the course of the evening.

Among the first to take the floor was Mr. Winfred Wright, a man whose very presence felt like the living memory of Marion Street itself. Hesitant at first, he explained, "Public speaking makes me nervous. But when a lifelong friend called me 'Mr. South End,' I knew I had to come."

Mr. Winfred Wright: Raised on Marion Street, Called by the South End

Mr. Winfred states, “From our home, we had a perfect view of the neighborhoods, rhythm, and life.”

Photo by Robert “Doc” Washington Photography

From his childhood porch on Marion Street, young Winfred had a front-row seat to the soul of the South End. He spoke with warmth about the Emile School, the Kerr Center, and Macedonia Baptist—not as buildings, but as sacred spaces that had helped raise generations.

"Turn the corner onto Chestnut and you could see everything," he said. "The church, the school, children playing games like marbles, hopscotch, four square, and shooting basketball. Our neighbors raised us as much as our parents did."

He recounted the excitement of homecoming Saturdays, when music from student musicians practicing for halftime shows filled the air. He described the Kerr Center as a place of dance and joy, where couples met and kids found their rhythm. "It wasn't nostalgia," he said. "It was dignity, it was survival, it was us."

Wright spoke of the educators at Emile who made miracles out of worn books and castoff materials. "They taught excellence without resources. They taught us to stand tall when the world tried to shrink us."

The crowd sat still, reverent. Wright's words became an anchor for the evening, grounding the future in the soil of shared memory.

Mrs. Paula Jefferson: The Voice of the Barbecue Pit and the Bottom

Born in 1962 at the same hospital as local historian Marla Dianne Mills, Mrs. Jefferson grew up on Newton Street near the famed cardboard sledding hill off Highway 71. Her father, Thomas Jefferson, was known not only for his work on Highway 71 but for his in-ground barbecue pit that drew neighbors like a magnet.

"My daddy didn’t cook for himself. He cooked for the people. The smell of meat on the smoke was our invitation to gather," she recalled.

Jefferson summoned the names of forgotten heroes—parade queens, church mothers, and local icons like the Lowe brothers, the Reed brothers and Mrs. Ruby Johnson.

Mrs. Bernie Jackson: “We Had Everything We Needed” — Raised Near MLK, Rooted in the South End

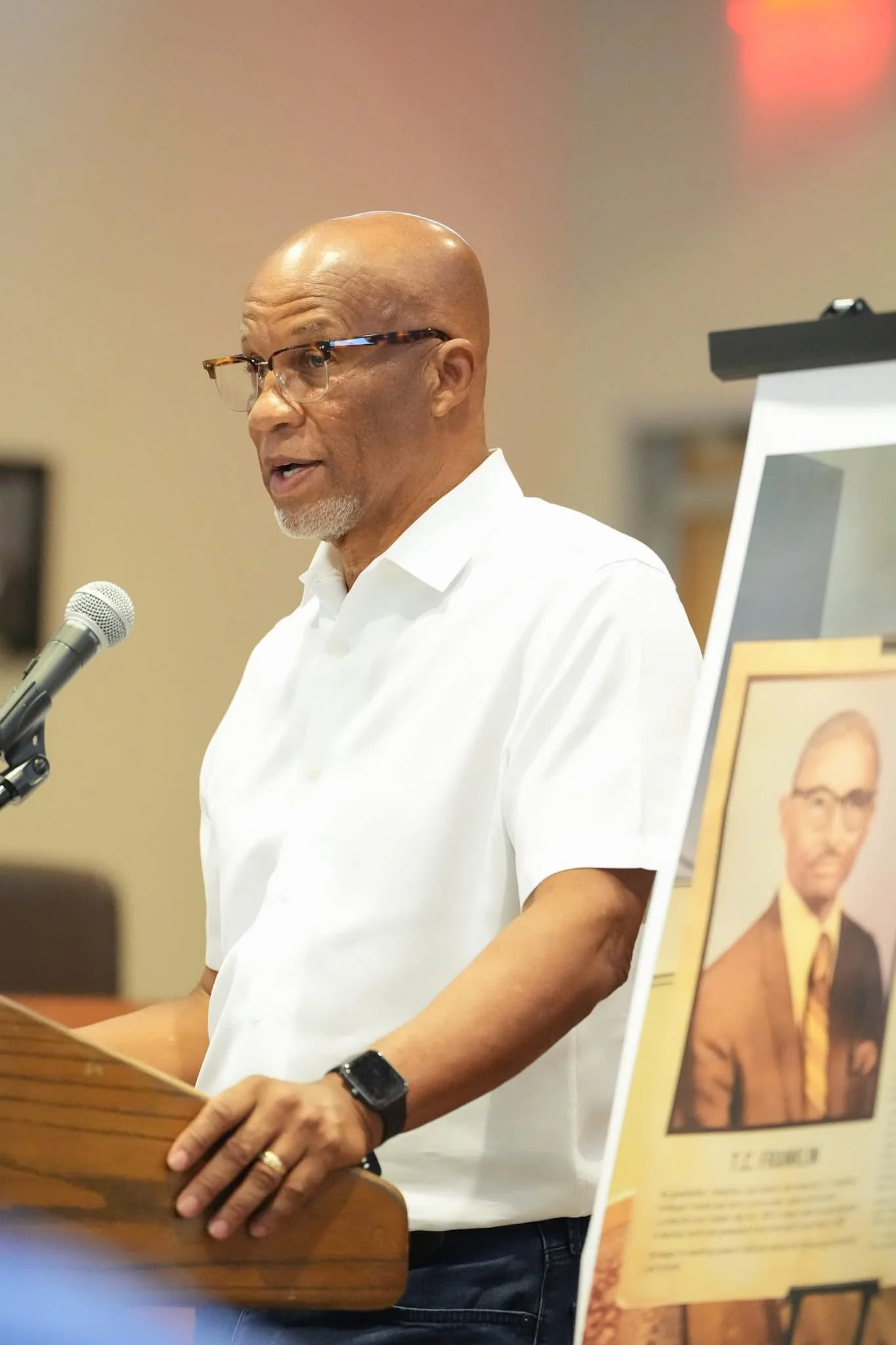

According to Mrs. Jackson, "We didn’t have to go across town for anything. We had everything we needed—right here."

Photo by Robert “Doc” Washington Photography

Mrs. Bernie Jackson grew up in the South End of Bastrop, near what is now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, at a time when Black neighborhoods were anchored in mutual care, education, and accountability. She was a member of the second-to-last graduating class of Emile School, a once-segregated institution that laid the foundation for generations of excellence.

Chestnut Street marked the boundary line. “If you crossed over Edue, you were in trouble,” she recalled. “That ended the South End.” But within those borders was a rich, self-sustaining world. “We had our barbershops, our teachers, our stores, and we had people who looked out for us.”

She fondly remembered neighborhood figures like Mrs. Katherine Robinson and Mrs. Whitley Avery—unofficial sentinels who would call your mama before you ever made it home if you stepped out of line. “Everybody looked out for everybody,” Mrs. Jackson said. “We felt safe moving around. We were protected.”

But it was education that stood as the community’s highest value. Her father was a close friend of Professor T.C. Franklin, a revered local educator whose home overflowed with books. “I had never seen so many books in my life,” she said. “There were books everywhere—and I remember thinking, this is what learning looks like.” That visit sparked a love for reading and set a lifelong standard: education is how you change your life.

Her memories are full of faces and places—Quinn White, her classmate and neighbor, who would walk part of the way home with her in the fading light; Mr. Ross and Mr. Russ, the neighborhood barbers; Miss E and other nurturing figures who made up the spiritual and social fabric of the South End.

Reclaiming the South End: The Community Responds

As the evening unfolded, more voices filled the room. Artists, educators, pastors, young professionals, and elders shared dreams and concerns. A local therapist emphasized mental health and family restoration. An educator called for youth programming rooted in Black history. A resident suggested a kickoff block party at the Kerr Center—potluck-style, under the shade of tents.

Others spoke of long-gone barbershops, Black-owned businesses downtown, and elders who had held onto land since Reconstruction. A chorus rose against gentrification, with several insisting that preserving identity is the best defense against displacement.

There was talk of signage, of designated district boundaries, of art installations and festivals. But more than that, there was vision. A vision of unity not just among the Black residents of the South End, but of a city willing to honor its shared history.

As the meeting closed, volunteers signed up for committees. QR codes were scanned. Young adults embraced elders. And Council Member Lowe’s words lingered: "This is not about what we remember. It’s about what we build."

Indeed, on that humid July night in Bastrop, the South End did more than speak. It sang.